Details of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement between the US, Japan and 10 other Pacific Rim nations have yet to be revealed, but one certain element in it will be a commitment to follow the ILO 1998 Declaration on Fundamental Principals and Rights at Work. Since 2007, the US has been required, under its own domestic legislation, to include discussions of labour standards in its trade negotiations. The ILO declaration, which covers child and forced labour, discrimination, the protection of migrant workers and the right to unionise, is invariably the basis for such discussions.

Yet, like all trade agreements, the strength of participants’ commitments to comply with ancillary matters is questionable. Although we already know that the TPP includes a disputes clause and a mechanism involving a panel of three international trade and subject matter experts to review the compliance problem, the record of previous trade agreements reveals a great reluctance to trigger international disputes over labour matters. In only one previous case —between the US and Guatemala —has a dispute been pursued to even bilateral talks and the matter remains unresolved after seven years of dispute settlement discussions.

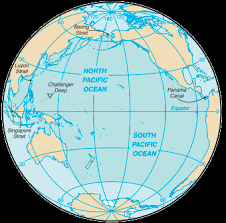

Governments frequently act as though they are responsible for the generation of international trade when, of course, they are the bodies erecting barriers to it. They impose tariffs and a wide range of regulatory impediments to restrict imports and manipulate their exchange rates to favour their domestic economies. All that trade agreements do is take apart the barriers that the governments initially imposed. The true purpose of TPP is, of course, to limit the hegemony of China —particularly across Asia —and, as such, represents the first trade agreement ever concluded between the USA and Japan. It may have an impact on international employers by, for instance, putting pressure on the Vietnamese government to allow free trade unions to operate and, probably, by relaxing rules on intra-company transfers and recruitment across national borders. However, it is also likely to pressure the Chinese government to drive their huge domestic companies to become multinational. This would be a major challenge for major western brands —and particularly jobs in the largest US corporates.