Hunan, China

It’s all a lost opportunity. The beautifully designed buildings – made to look like porcelain bowls in the ceramics centre of Li Ling in China’s Hunan Province. Then inside them the unimaginative rows of fine bone China in each space allocated to individual manufacturers. At those prices they do not even retail, let alone attract the interest of exporters and wholesalers. Then you reflect on the long broken road from Zhu Zhou to get there. A road so full of deep potholes even large tipper lorries have to crawl and weave. By the time the potential buyer of porcelain gets to the city they are asking themselves what chance would their purchases have of reaching the next city intact – let alone half way around the world.

So many things in China are ambitious in intention, but fail on the detail and realization. It is like the interestingly designed “Bamboo Museum” in Changsha. Free admission ensures school parties and coach trips fill it up each day – but the internal displays are needlessly disappointing. There are a few bamboo strips dug up locally, a history of paper making (which is incorrect) and some photos with explanations in Chinese and a curious English not translated by a native English speaker. Then upstairs a display of ceramics and metal bells. They obviously ran out of ideas for the second floor. What is missing, of course, is the very thing you would expect in the semi-tropical area of a communist state – the use of bamboo by ordinary people in the last few centuries. Bamboo has been used by farmers since the dawn of history – for things like fences, field pipes and roofing supports for barns. In construction it was used for scaffolding right up until recent years.

So I descend to the colourful friendly shop where I enquire about bamboo’s greatest modern emanation – a soft, but strong cloth that is great for shirts, socks and underwear because it has natural antibiotic properties and therefore stops the sickly odour of sweat. The counter assistants point across to a display of silk items and are strangely confused – with glazed over eyes – when I try to explain that bamboo can actually also be a textile.

China is marching forwards at such a rapid pace it is leaving its rich history behind, but in doing so also ignoring the potential that geography and history can give it commercially. The vast Xiang Jiang river runs through Changsha, but locals will give you every obscure and unconvincing excuse why it is not possible to take a boat trip on it. It is busy with barges, but I have yet to see one pleasure boat or private cruiser moving between its massive banks.

Take a trip too on the wide highway that stretches north from this city of seven million people and after a few miles the high rises peter out and the road narrows to a pitted track. Here the countryside is magnificent – verdant green paddy fields merging into natural woodland and small drumlin hills. The rich red (and even mauve) soil is dug up everywhere within a hundred metres of the road. But beyond it is a peaceful paradise that China has almost forgotten.

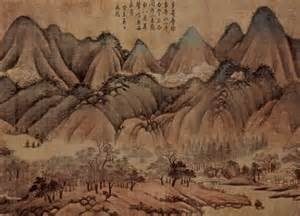

Or take the road south from Zhang Jiajie along the Li Shui river valley (some distance from the ugly tourist-swarming limestone stacks further north). Either side are graceful mountains that the Chinese seem to hardly value. Here the scenery and even housing looks remarkably close to the Spanish side of the Pyrenees – a long way from all the typical photos you see of China. In fact, most of this part of China is very European – but with a deeper, purer, lush and verdant aspect and in the such a subtropical zone it is hard to see why people feel so drawn to cities as crops grow so readily in the rich soils and moist climate. In this inviting landscape endless successions of people must have done great deeds, written great thoughts, drawn, invented, loved, dreamed – but who now would know?

Maybe it takes a foreigner to remind a people of the losses that progress is bringing with it and the potential that its own history provides for its future. I wonder in amazement at the clean roads, each tended to by an individual road sweeper. I warm constantly to the kindness shown by everyone I meet (in spite of their apparent impatience and disposition to shout rather than to talk). I admire the sheer industry and optimism of a people speeding to a future they only vaguely visualize as more of everything and an end to past deprivation. But I feel sad at the destruction that comes in its wake – to the mother China, the place where countless peace-loving civilizations have left their mark.

I suppose the same goes for many other countries in the developing world. It is certainly true of individual companies. Just look at the “about section” on corporate websites. The mammoth effort of founders and those who have built the onward business is often summarized into one or two paragraphs. Few companies really concern themselves about their past – unless it can be exploited for the sake of a brand or momentary point of rivalry against an upstart competitor. But history and the aesthetics of landscapes are not just a commodity that can be bought and sold, not a switch that can be turned on and off like a light, not something that can be seen in part, without attention to the whole – but they are too often, all too readily treated as more worthless than a discarded cloth or the torn-off wrapping around a chocolate bar.